I haven't read this one for quite a while and I'd forgotten just how much there is to talk about in it... I'm bound to miss something! The Last Hero was originally released as an illustrated story - the front cover says 'A Discworld Fable' - and that's the version I have. The story is told more briefly and simply than the longer novels (for example, Carrot goes on a life-or-death mission to save the world without, within the narrative at least, saying goodbye to his girlfriend) and illustrated by Paul Kidby.

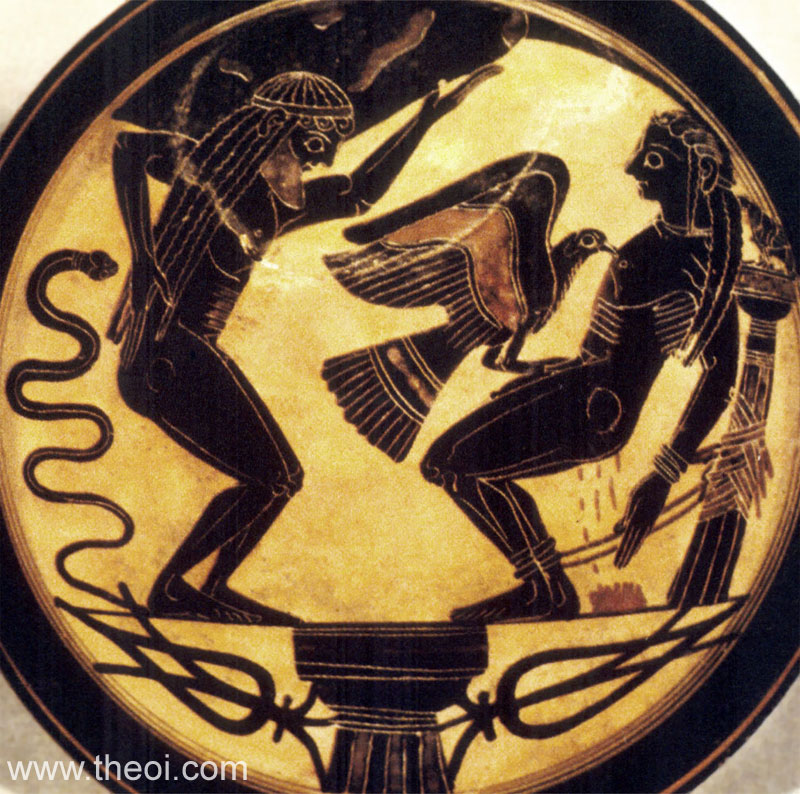

I haven't read this one for quite a while and I'd forgotten just how much there is to talk about in it... I'm bound to miss something! The Last Hero was originally released as an illustrated story - the front cover says 'A Discworld Fable' - and that's the version I have. The story is told more briefly and simply than the longer novels (for example, Carrot goes on a life-or-death mission to save the world without, within the narrative at least, saying goodbye to his girlfriend) and illustrated by Paul Kidby.OK, well, first, the basic set-up - which is based on the myth of Prometheus, here renamed 'Mazda' (I'm not sure if that's significant, it doesn't mean anything to me) (Edit: it would appear that 'Mazda' is a Zoroastrian god associated with fire, which makes sense - see comments below). Prometheus, in Greek mythology, stole the secret of fire from the gods, and was punished by being chained to a rock for all eternity, with an giant eagle eating his liver every day (the liver regrowing overnight). The main source for his myth is Hesiod, who also has Heracles (Hercules) rescue Prometheus after a (fairly long) period of time. The Discworld version is very similar, though simplified (in Hesiod, Zeus has deprived men of fire in punishment for another trick of Prometheus', which is why it must be stolen back again) and the story of Mazda is accompanied by an

illustration based very closely on this sixth century black figure vase, but incorporating the Discworld chief god Blind Io.

illustration based very closely on this sixth century black figure vase, but incorporating the Discworld chief god Blind Io.Ironically for one of the shortest Discworld novels, the themes of The Last Hero are those of epic poetry - mortality and the immortality that may be gained if a hero is remembered in song. Although the unnamed singer and some of the aesthetics - the heroes' fur costumes and Viking conceptions of both funerals and the afterlife - owe more to Beowulf (which is Anglo-Saxon) and probably Wagner, the problem of mortality is central to a lot of epic poetry. Perhaps it's not such a strong theme in the Odyssey, though it is there, especially in Odysseus' journey to the underworld, and the Song of Roland is quite keen on the idea of the glorious death in battle, but the Epic of Gilgamesh is about the search for immortality, the Iliad is all about problematizing the values of long life and peaceful death against a short life with poetic immortality and Beowulf itself sees its hero grow old and die.

Death is not something that is often embraced by Discworld characters, the series being built on Rincewind, a hero who is pretty determined not to die any time soon. However, it is occasionally embraced by elderly characters, like the witch in Mort or, to some extent, Miss Flitworth in Reaper Man, so it would not be entirely surprising to see the elderly Silver Horde of heroes of the barabarian variety die willingly. However, this is not what they have in mind. The Silver Horde are determined to rage against the dying of the light and are extremely angry at the gods for allowing old age and quiet, non-heroic death to overtake them, so they plan to return fire to the gods, with interest - interest in the form of a very large explosion.

Unfortunately, this explosion will destroy the world, so a different sort of hero has to be sent to stop them. Although they call themselves barbarians, the Silver Horde are pretty similar to Greek heroes - the job of a hero consists of murder, theft and pillage. The difference between them and Greek heroes is that they don't include rape, and don't have to, since the women they 'ravish' are apparently quite willing. (This is, of course, because modern readers tend not to sympathise with rapists). The hero who must stop them is Carrot, a more modern hero - a man with a steady job protecting the public whose idea of heroism is to save lives whenever possible, not take them. (The Dark Lord Evil Harry is also a more modern phenomenon - he belongs in 20th/21st century fantasy fiction, thanks to Tolkien).

The gods of the Discworld, as I noted in the last post, also have a distinctly Classical bent.

This is Paul Kidby's illustration of some of the Discworld gods - (l-r) Offler the Crocodile God, not actually an Egyptian deity (as far as I remember) but clearly inspired by Egyptian deities which included jackal-headed, dog-headed and eagle-headed gods, Flatulus God of the winds (ha ha ha, but note the Romanised name), Fate, Urika (no obvious Classical origin, but the name sounds like the Greek 'eureka!', I have it, shouted by Archimedes in the bath and possibly explaining why she's goddess of saunas), Blind Io (basically Zeus/Jupiter, but with the extra element of the floating eyes), Libertina (Goddess of apple pie among other things, which is best not to think about), The Lady (Luck/Fortuna), Bibulous, Patina, Goddess of Wisdom (Athena/Minerva, she's wearing Athena's helmet), Topaxi (little red one down at the front, no idea what he's about), Bast (cat goddess at the back, actually an Egyptian goddess though not originally associated with things left on the doorstep or half-digested under the bed, that's just modern domestic cats) and Nuggan (who comes up later in the story). Later, we see the blacksmith god, who is unnamed, but Hephaestion, Vulcan and Wayland (Celtic) are actually name-checked here (along with Dennis who I think is... less genuine).

As you can see, their home, Dunmanifestin (Dun manifestin', like dun roamin') also looks very Greek. Kidby's illustration of the outside of Dunmanifestin includes architectural elements from various religions - Egyptian, medieval Christian, Aztec, even the Easter Island faces - but the majority is vaguely Greco-Roman and the top area, where we see the gods play their games, looks definitely Greek. In the western imagination, polytheistic religion is Greco-Roman, with just a hint of Egyptian.

A lot of the story is about the fact that the world the barbarians lived in is slipping away, and in many ways the minstrel they bring along to witness and tell of their great deeds epitomises that. (The Horde have heard of the Muses, but they've either misunderstood their purpose - ancient poets don't claim to be witnesses of mythology, they are inspired by the Muses - or simply don't trust them to tell it right). The Horde need Homer or the author of Beowulf, but they've got Shakespeare - great with sonnets, not so good at epic. (They have been ruling the Agatean Empire, but rule out poets there for not writing more than 17 syllables - to the western imagination, all Asian poetry is haiku. This is entirely inaccurate, but there we have it). Over the course of the story, however, the minstrel becomes somewhat converted, though the emphasis on the music he plays at the end may imply he is going the route of Wagner rather than Homer.

As the minstrel tries to understand why the barabrians are doing what they're doing, he quotes the great conqueror Carelinus, who conquered all the known world except Fourecks and the Counterweight Continent (Australia and Asia - the Discworld does not appear to contain America, of which make what you will) and wept when he saw there were no more worlds to conquer - i.e., Romanised name notwithstanding, Alexander the Great. The line about Alexander weeping is of uncertain but not ancient origin, though it may stem from Plutarch's suggestion that, when he heard there were infinite worlds, Alexander wept because he had not yet conquered one. Cohen, though he thinks weeping is sissy (proving himself not to be a Greek hero, as Achilles and Odyseeus regularly burst into tears) thoroughly agrees with this sentiment.

There are some nicely satisfying moments for Classicists in this book. There's the obligatory rescue of Mazda of course (the eagle won't know what stabbed it with a big sword). Even better, while Ponder Stibbons struggles to come up with a way to stop the spaceship crashing when the

designer (Leonard da Quirm, the Disc's greatest genius), the Patrician realises they should pull 'Prince Haran's Tiller' because Prince Haran was a legendary Klatchian hero whose ship had a magical tiller (I can't remember the real-world origin of this story at the moment, though 'Kltachian' suggests Arabian Nights).

designer (Leonard da Quirm, the Disc's greatest genius), the Patrician realises they should pull 'Prince Haran's Tiller' because Prince Haran was a legendary Klatchian hero whose ship had a magical tiller (I can't remember the real-world origin of this story at the moment, though 'Kltachian' suggests Arabian Nights).Leonard da Quirm ws a genius, but hadn't quite got the hang of smiles. Illustration by Paul Kidby.

The last page of the book says 'No one remembers the singer. The song remains'. Homer, if he was a real person, might not approve entirely, but the story certainly comes to the same basic conclusion as the Iliad - that there is something to be said for a glorious death if it is remembered in song. The Horde, however, are considerably older than Achilles and although 'second star to the right and striaght on till morning' is pooh-poohed as a ridiculous method of astronavigation, the Horde do ride off on the horses of the Valkyries into the stars, with Death refusing to confirm whether they are alive or dead. It's a beautiful story, beautifully illustrated, and provides a suitable send-off for the now out-dated Silver Horde - for just as they have no place on the Discworld any more, modern tastes tend away from the barbarian hero, and thoughts turn more towards the philanthropic, self-sacrificing hero of Carrot's mould.

Edited to add: it's been pointed out to me below that I missed out the heroic trio's motto - Morituri Nolumus Mori, which roughly translates as 'we who are about to die don't want to die'. Rincewind suggests this, of course, demonstrating his well-known ability with languages as well as his fervant desire not to die yet. No one else seems to object to it though, and it's a rather good motto, though not as good as the dwarf battle cry which reworks the Klingon 'Today is a good day to die' into 'Today is a good day for someone else to die'...

No comments:

Post a Comment