Of the many dangers that plague commercial airplanes, icing stands out as one of the most treacherous. The threat of ice build-up on aircraft surfaces has been known and studied for decades, but now NASA is putting new effort into understanding a different kind of ice danger.

Of the many dangers that plague commercial airplanes, icing stands out as one of the most treacherous. The threat of ice build-up on aircraft surfaces has been known and studied for decades, but now NASA is putting new effort into understanding a different kind of ice danger.A well-known icing problem involves ice forming on wings and other surfaces that can cause drag and power loss on an aircraft. A different threat emerges when airplanes fly into clouds with high ice content found near thunderstorms in very high altitudes. Ice particles, once thought benign because they would simply bounce of airplane surfaces, can accrete deep inside jet engines and shut down the power. This is called “ice particle icing,” to distinguish it from icing caused by super-cooled liquid droplets, which typically occurs at lower altitudes.

There have been more than 240 icing-related incidents in commercial aviation since the 1990s, of which 62 resulted in power-loss likely due to ice particle icing, according to a study authored by Jeanne G. Mason, J. Walter Strapp and Phillip Chow. This condition is difficult for pilots to identify because in many cases the ice is forming only inside the engine, without any visible icing on the wings.

Researchers at NASA’s Langley Research Center are taking a closer look at the phenomenon, which is considered a significant threat to commercial airlines. NASA scientists are developing ways to identify the conditions that cause ice particle icing to better warn pilots about where this might occur.

“It’s something that hasn’t been explored much,” said Chris Yost, a NASA contractor and research scientist with Science Systems and Applications Inc. in Hampton, Va. Yost said his research is at a preliminary stage now, focused on pinpointing the types of clouds connected with ice particle icing. He will present his latest results at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting in San Francisco on Dec. 14.

“These are deep convection, thunderstorm-like clouds,” Yost said. “Thin, wispy cirrus stuff is not so much a problem.”

NASA research is aiming to improve weather forecasts that could steer pilots away from trouble. Building on tools developed to detect surface icing conditions, NASA scientists are using cloud observations from two satellites, CALIPSO and CloudSat.

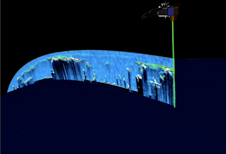

CALIPSO and CloudSat fly only seconds apart on the same orbit. Together they provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. In preliminary research, CloudSat and CALIPSO have been used to build on previous methods of identifying the type of moisture particles that lead to ice particle icing problems. CALIPSO’s lidar is used to create a vertical profile of clouds to accurately measure cloud height while CloudSat provides the estimates of ice concentration in those clouds. Together the two instruments provide very detailed information about the vertical structure of clouds, and the ice particles within them.

Yost and other SSAI researchers have been working with Patrick Minnis, at NASA’s Langley Research Center, on incorporating CALIPSO and CloudSat data into forecast models with the goal of identifying potential ice particle icing conditions.

NASA’s research on ice particle icing began in 2005 with the integration of cloud data from the NOAA satellite GOES. This was followed on by a field experiment on NASA’s DC-8 in 2007 to compare ice particle measurements from GOES with actual aircraft measurements. While this data significantly increased researchers understanding of the icing process, the integration of CALIPSO and CloudSat data has vastly enhanced the ability to see what is within the clouds.

NASA’s research on ice particle icing began in 2005 with the integration of cloud data from the NOAA satellite GOES. This was followed on by a field experiment on NASA’s DC-8 in 2007 to compare ice particle measurements from GOES with actual aircraft measurements. While this data significantly increased researchers understanding of the icing process, the integration of CALIPSO and CloudSat data has vastly enhanced the ability to see what is within the clouds.Yost is currently comparing satellite records of weather conditions with the coordinates and time and date of specific airplane power-loss incidents in recent years. The research could illuminate more specifically what type of weather leads to ice particle icing and whether ice particle icing was a factor in these accidents. Future plans include flights with NASA’s DC-8 to take on-board measurements as a comparison point for CALIPSO and CloudSat observations.

Minnis described the group’s ongoing work as a first cut, but envisions it leading to better forecasting of potential ice particle icing conditions in the future.

“The ultimate goal of the project is to be integrated into existing forecast models and eventually into the NextGen (Next Generation Air Transportation System) cockpit system,” Minnis said.

Aviation safety organizations around the world are presently working with the ultimate goal of being able to accurately forecast inflight icing conditions in real-time for pilots. The integration of NASA satellite data into forecasting models is bringing them closer than to that goal, step by step.

Related Links:

> NASA Langley Cloud Radiation Group

> Advanced Satellite Aviation Weather Products (ASAP)

> NASA's Applied Sciences Program

View this site car shipping car transport auto transport auto shipping

No comments:

Post a Comment