Since it's Roman Catholic Palm/Passion Sunday, and the start of Holy Week, this seemed like a good time to look at Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, which is that rare thing - a production that includes spoken (subtitled) Latin that is not part of a church service, nor does it appear in a comic context (see Chelmsford 123 and Blackadder Back and Forth).

Since it's Roman Catholic Palm/Passion Sunday, and the start of Holy Week, this seemed like a good time to look at Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, which is that rare thing - a production that includes spoken (subtitled) Latin that is not part of a church service, nor does it appear in a comic context (see Chelmsford 123 and Blackadder Back and Forth).Before we get on to the Latin, though, there are several other points of interest in this film. The second biggest controversy at the time it was released revolved around the film's use of extreme violence, and it remains the most successful R-rated film to be released in the United States. I didn't see the film in the cinema and put off seeing it at home for ages because I'd heard such horror stories about it. When, eventually, I did see it, I didn't think it was that bad after all, but perhaps if I'd been stuck in a cinema, watching it on the big screen, I would have felt differently.

What marks Gibson's film out from Jewison's or Zeffirelli's is that Gibson's version of the story is very much a personal act of faith. This is not to say that faith was not a factor in the other two - I would not dream of presuming to make statements about the extent or nature of Jewison or Zeffirelli's religious faith - but whereas their films presented an attempt at an historically accurate re-telling of the Gospels in Zeffirelli's case, and an exploration of the human Jesus told chiefly from Judas' point of view in Jewison's, Gibson's film is basically an extension of the Catholic tradition of meditating on the Stations of the Cross during Lent. This tradition emphasises the significance of the physical suffering of Jesus and encourages meditation on, well, how horrible the whole thing is. This is part of the reason for Gibson's unusual level of attention to physical suffering in the film.

There are other reasons as well. Isaiah 52:14, often interpreted as a prophecy concerning the suffering of Jesus, says that His appearance was 'disfigured beyond that of any man', which can be interpreted as a reference to the result of extreme violence. Perhaps more importantly, the extent of the violence seen in the film justifies some of the other events of the film. The first beating, for example, which as far as I can tell does not have its origin in the Gospels, provides Judas with sufficient comprehension of what he has done that it drives him to suicide (along with some bizarre devil-children - more on them below).

There are other points which do originate in the Gospels or in church tradition that make more sense in the context of the film's extreme violence. Whereas other films about Jesus shy away from depicting miracles, or depict only those which are smaller and less showy (Zeffirelli, for example, depicts healings but not Jesus walking on water, though he does include the feeding of the five thousand) Gibson, more interested in the spiritual story than in a more secular interpretation, includes just about all elements of the Passion story, from Pilate's wife's dream to the removal and replacement of the ear of a soldier called Malchas, which is very rarely dramatised. So Gibson also includes Veronica offering Jesus a cloth which is left with the imprint of His face - which suddenly makes a lot more sense when His face is shown covered in copious amounts of blood.

Most importantly, according to the Gospels, Jesus died after only 3 hours - crucifixion normally takes days. The traditional explanation for this, which seems logical enough (well, the physical explanation, divine intervention being understood as the real reason), is

that Jesus had been so badly beaten and tortured before He was crucified that He was dying already, and this is stated specifically in the traditional prayers that are said at the Stations of the Cross. So the violence inflicted on Jesus has to be fairly extreme, to demonstrate that His body is already dying before it is nailed up.

that Jesus had been so badly beaten and tortured before He was crucified that He was dying already, and this is stated specifically in the traditional prayers that are said at the Stations of the Cross. So the violence inflicted on Jesus has to be fairly extreme, to demonstrate that His body is already dying before it is nailed up.Having said that, some of it is a bit excessively extreme. Why on earth the unrepentant robber has to have his eyes plucked out by ravens or crows I do not know - this is pure invention on Gibson's part and totally unnecessary, as is Judas resorting to taking rope from a dead donkey (or was it a goat? No, I think it was a donkey) to hang himself with (as if hanging himself wasn't bad enough already). And I'm not sure Jesus needed to be beaten up quite so often, considering the flogging could easily have killed him by itself. Talking of the flogging - that wasn't nearly as bad as I'd expected - there were a couple of nasty shots of flesh being torn away, but for the most part we saw only the soldiers and Jesus' hands or his face, like most filmed flogging scenes, and for much of it we followed Mary away from the scene all together.

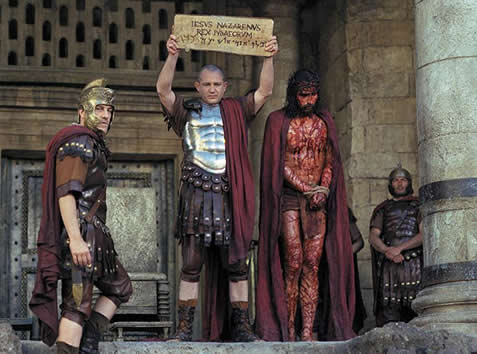

Anyway, the more important point as far as Classics is concerned (don't worry, I haven't forgotten I'm supposed to primarily talking about Classics!) is: is all this violence historically accurate? I think, for the most part (horrible bird-related eye-gouging excepted) it is presented in a reasonably accurate way. It is made clear that not all criminals are treated with this degree of cruelty, as several soldiers demand that the flogging/beating be halted at various points, and the other two criminals look absolutely fine (apart from being crucified, that is). This fits nicely with the idea that Jesus was more badly beaten than usual, and that's why He died more quickly than usual. On the other hand, it's equally clear that no one is especially surprised by the treatment doled out to Jesus, and that the soldiers will not get into trouble for it - this is, after all, the civilisation that gave us the gladiatorial arena. Pilate's expression when he sees Jesus post-flogging, crown of thorns and all, sums it up perfectly - he raises his eyebrow in mild surprise at the extent of Jesus' injuries and he treats Him with sympathy and concern, but he is not especially shocked or outraged - this is more exaggerated than usual, but nothing out of the realm of his experience. This seems about right for ancient Rome (or rather Judaea).

Of course, the most significant use of Classics in this film relates to language, and this is something I'll talk about more in an article I'm writing at the moment (which will be published online). I'll go over the main points here as well though. Firstly, and most obviously - for much of the film, Pilate, Jesus and the various other characters are speaking the wrong language. Gibson shot the film in three languages - Latin, Aramaic and Hebrew. Aramaic was the language of the Jews in Palestine at that time, Latin the language of the Romans, and Hebrew I think was chiefly a religious language but I'm not sure. I can't tell the difference between Aramaic and Hebrew, I'm afraid, so I don't know when they switch between those two but, of course, I can tell when they switch into Latin.

Trouble is, the lingua franca of the East of the Empire at that time wasn't Latin, it was Greek. Scenes between two soldiers who both come from the Latin West might reasonably show them speaking Latin, and Pilate and his wife might communicate with each other in Latin, but any scenes in which Pilate communicates with the Jews - or even with large groups of soldiers, if they come from various parts of the Empire - should have been performed in Greek. Not only that, but the Gospel of John actually states that the sign placed above Jesus on the cross - reading 'Jesus

of Nazareth, King of the Jews' - was written in Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Gibson shows only Latin and Hebrew. Gibson claimed that the reason for using the ancient langauges was historical accuracy, but it wouldn't take much research to establish that Greek would be the common language for communication between different groups - any ancient historian could have told him that (and he's hardly known for his attention to historical accuracy anyway). So why the inaccuracy?

of Nazareth, King of the Jews' - was written in Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Gibson shows only Latin and Hebrew. Gibson claimed that the reason for using the ancient langauges was historical accuracy, but it wouldn't take much research to establish that Greek would be the common language for communication between different groups - any ancient historian could have told him that (and he's hardly known for his attention to historical accuracy anyway). So why the inaccuracy?I have a few ideas, which I'll talk about more in my article. Basically, I think Gibson is a little too attached to his Catholic upbringing. He wants Pilate to say 'Ecce homo!', not 'Idou ho anthropos!', and he wants to hear Latin, the language of the Catholic Church, not Greek (the language of the Greek Orthodox Church, presumably). Perhaps this is also why he has the two other criminals carry only the cross-bar of their crosses, as depicted in Jesus of Nazareth and as some historians argue was the case in reality, while Jesus Himself has to carry the whole enormous cross, as depicted on many, many illustrations of the Stations of the Cross (which are on the walls of every Catholic church). (Of course, this also makes it easier for Simon of Cyrene to help carry the cross, so that might explain that one).

Gibson also plays with the language a bit to emphasise Jesus' divine nature - whereas Pilate communicates with all other Jewish characters in Aramaic (I'm very skeptical that a Roman governor would have bothered to learn Aramaic) when Pilate starts to question Jesus in Aramaic, Jesus replies in Latin. Presumably this is meant to acheive the same goal as the earlier, rather ridiculous flashback sequence where, as Mark Kermode puts it, Jesus invents the kitchen table - it demonstrates that Jesus has access to knowledge others around him do not have, because he is divinely omniscient. All this is at the expense of everyone else around him, who are confined to Aramaic and Hebrew.

The other oddity, language-wise, occurs in the flogging scene, in which the Latin subtitles suddenly disappear. The Aramaic/Hebrew (sorry, no idea which it is!) is still subtitled but the taunting Latin of the soldiers, and the counting of the strokes of the whip, is in unsubtitled Latin. Gibson famously wanted the whole film to be shown without subtitles - perhaps to produce a more immersive experience? - and was persuaded otherwise, but this bit was left. Why?

Perhaps the idea is to increase our incomprehension and confusion, as we watch the flogging from Mary's point of view. The use of Latin here is not so odd - perhaps the soldiers all come from the West - and Mary would be unlikely to speak Latin fluently, so perhaps this is supposed to put us in her shoes. The soldiers aren't saying anything terribly strange or exciting - I'm not used to translating spoken Latin (even in church they give you the words) but I caught phrases like 'enough!' and the counting, which are obvious enough from context, taunting phrases like 'facta non verba' (deeds not words) and, at one point as Jesus tries to get up from the floor, 'credere non possum', I don't believe it. I can only assume that Gibson wants to make the soldiers seem more alien and Jesus more human and closer to us by allowing us (his non-Latin speaking audience that is, which may be the majority) to understand Jesus but not the soldiers.

Oh, and the pronunciation of the Latin, often by Italian actors, tends to towards the Italinate - which gives us a slightly bizarre situation in which the Jewish Aramaic pronunication of 'Caesar' (like the German 'Kaisar') is closer to the way Caesar probably said that the the Latin Romans' (which is more like 'Che-sar').

I actually like The Passion of the Christ a lot, it's very moving and the shot of Mary sitting in the traditional pieta position and staring straight at the camera is quite unnerving (in a good way). I think it loses the plot, though, whenever it strays too far from either the Gospels themselves, or sensible extrapolation and enhancement of the Gospels. By

'sensible', I mean scenes like that of Mary seeing Jesus fall under the cross, and remembering seeing him fall as a child, and rushing to help him - although Mary's flashback and memory are invented, these seem like reasonable enhancements of the story. The slightly extended role for Pilate's wife, deeply affected by her dream, is quite nice too.

'sensible', I mean scenes like that of Mary seeing Jesus fall under the cross, and remembering seeing him fall as a child, and rushing to help him - although Mary's flashback and memory are invented, these seem like reasonable enhancements of the story. The slightly extended role for Pilate's wife, deeply affected by her dream, is quite nice too.On the other hand, the 'kitchen table' scene is pretty bad, and the strange, androgynous devil figure who stalks Jesus throughout the film and the creepy devil-children who hound Judas to his death (and who look like something out of Don't Look Now) are just strange and out of place. Perhaps Gibson wanted to emphasise the Catholic doctrine that Judas' worst sin was despair, thinking he could not be forgiven, by having the devil drive him to suicide, but it just doesn't work, and Judas has quite enough reason for despair already. The Gospels do describe Jesus being tempted by the devil, but way back at the begining of His ministery, not at the end. The scene in the Garden of Gethsemane would be much more powerful if it was solely about a man struggling with his conscience and determination, no devil figure required.

Other than that though, it is a beautifully made film (well, you know - the less gory bits are) and the music is great. The depiction of the Roman empire manages to emphasise the violence that TV and filmmakers are so fond of emphasising in Roman stories, but whereas most glamourise this violence, or use it like historical window-dressing, all over the place and sometimes without much rhyme or reason to it (Rome, I'm looking at you!) this film depicts that violence in a brutal and unforgiving fashion, without throwing it in to scenes where it isn't necessary.

One final niggle though - as I reached the end of the film, I remembered something else that stands out about it - this is the film that gives us Naked!Jesus! I'm sure Gibson was going for spirituality and new life, and the shot of the burial shroud deflating as the body disappears from it is beautifully done. I take the point that if the shroud is empty, Jesus probably doesn't have much else to wear, and it's very Gandalf-on-the-mountain-post-Balrog, etc etc etc. But Jim Caviezel is a very good-looking man, and even bearing all that in mind - it's Naked!Jesus! And he's really close to the camera - OK, you don't see anything, but you're pretty close to some upper thigh there. This does not make me reflect on the miracle of the Resurrection and is liable to result in a train of thought that would get one excommunicated. Surely they left Him a loincloth in the tomb? Or if not, God could just - I don't know - provide magic clothes?! Or He could wrap the burial shroud around Him, before wandering off? Naked!Jesus is just not the way to end such a deeply serious and genuinely moving film...

Edited to add: Having done a bit more research on this film for my article, consensus seems to be that the whips used on Jesus here are accurately portrayed, and soldiers quite often deliberately whipped victims to the point of death because they had to guard the cross until the victim died - the worse the scourging, the less time they had to spend hanging around by the cross. So the violence is pretty accurate. Also, victims would be naked during the scourging, so I should be grateful there wasn't even more nudity in the film.

No comments:

Post a Comment